The mining and milling of Canadian uranium contribute very few greenhouse gases to nuclear power’s already low emissions, a research group has found.

"People frequently think that nuclear power still emits a lot of greenhouse gases because of uranium mining, but what this study shows is that mining is a relatively small contributor to nuclear's overall emissions," said Cameron McNaughton, an environmental engineer with Golder Associates and adjunct professor in the U of S College of Engineering.

The study, supported by the Sylvia Fedoruk Canadian Centre for Nuclear Innovation at the U of S, was published online earlier this month in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Science and Technology.

"We found that the mining and milling of uranium contribute about a gram of greenhouse gases (as CO2 equivalents) per kilowatt-hour of power that comes from that uranium," said David Parker, who conducted the study for his master's degree, co-supervised by McNaughton and U of S professor emeritus Gordon Sparks.

By comparison, coal produces over 800 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour and natural gas about 500 grams, according to the 2014 U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The report cites a mid-range value of 12 grams of CO2 equivalent gases per kilowatt hour for nuclear power, similar to wind power.

"Saskatchewan has the highest grade uranium in the world, and the emissions from uranium mining in Canada are very, very low when compared to extracting fossil fuels," said Parker. "This is the first rigorous look at greenhouse gas emissions from uranium mining and milling in Saskatchewan, and is more detailed than the few studies that have been done before."

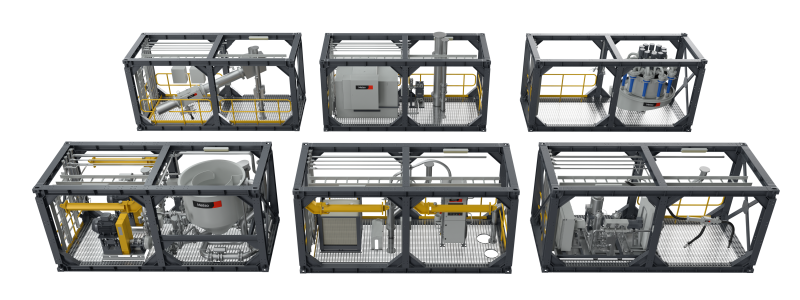

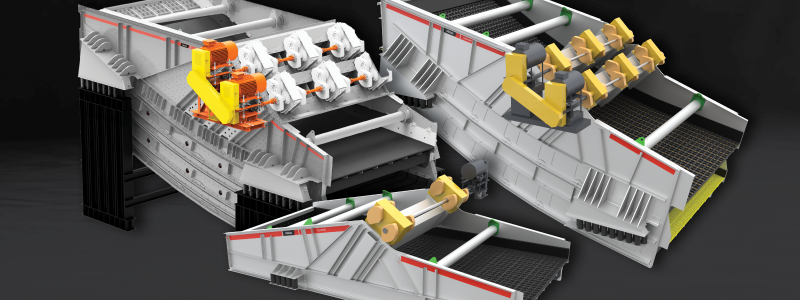

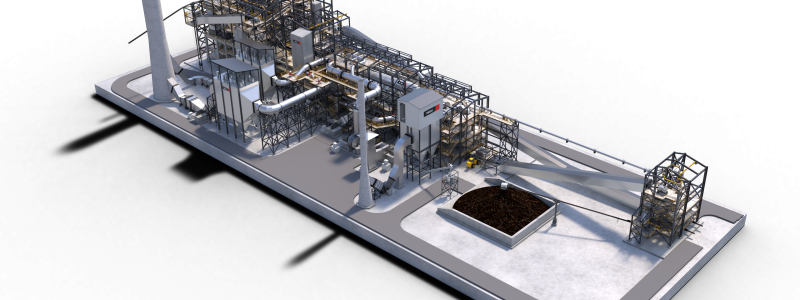

The study involved adding up the greenhouse gases emitted by everything used in the mining and milling of uranium at three Saskatchewan operations -- from the fuel used in heavy machinery and to power the mine and mill operations, to the concrete and steel used in construction, to the emissions from flying workers in and out of the mine sites. Even the emissions from the mining companies' head offices were tallied. The technique, called a life cycle assessment, followed a methodology laid out by the International Organization for Standardization.

"When doing life cycle studies it is really surprising how much data is required, and how difficult it can be to get all of that info," said Parker, who was able to use information supplied by uranium mining companies Cameco Corporation and AREVA Resources Canada, as well as databases that contain information about the greenhouse gas emissions for things like building materials.

The researchers hope to expand their life cycle assessment work in a number of directions, looking at the impact ore grade and different mining processes have on emissions, moving their analysis further down the nuclear fuel cycle, and broadening it to consider other environmental impacts beyond greenhouse gas emissions.

"Studies like this support the idea that nuclear can work with renewables as sources of low-carbon electricity," said McNaughton.

Story Source:

Materials provided by the University of Saskatchewan. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.