By Simon Matthis

President Donald Trump’s obsession with rare earth elements (REEs) — in Ukraine, Greenland, and most recently in his push for deep-sea mining — is not as eccentric or original as it might seem, at least not compared to many of his other political positions. It’s worth noting that the previous EU Commission’s raw materials strategy also placed considerable emphasis on developing rare earth production and, more broadly, critical metals.

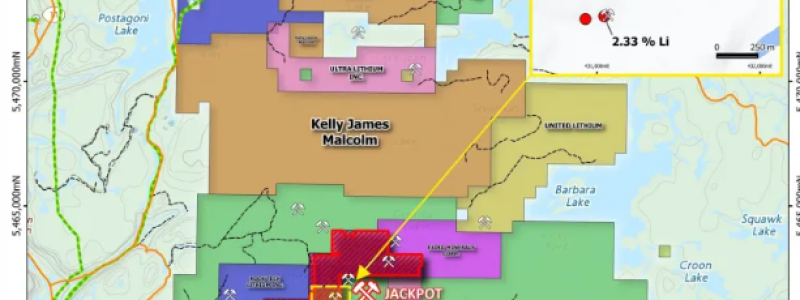

China is by far the world’s largest producer of rare earths, as well as many other metals classified as critical by the EU and other countries. Far from being restrained by this dominance, China is now explicitly using REEs as leverage in the ongoing trade war.

REEs are vital for the energy transition and are also used in numerous critical applications — electric motors, medical imaging and diagnostics, oil and gas refining, and computer and smartphone screens.

So, how will this anticipated surge in REE demand be met? The simple answer is: more extraction. However, extraction is associated with major environmental problems, including land use challenges — which should not be confused with climate change issues (a political topic subject to differing opinions).

A common misconception about rare earth elements is that they are rare — hence the misleading name. In fact, rare earth elements are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust, but they are seldom found in concentrated, economically viable deposits. Additionally, they are rarely located near the Earth's surface. Most extraction and processing of REEs also generate toxic and radioactive waste.

An even greater challenge lies in refining these materials, an area where China’s dominance is even more pronounced. Western countries lag far behind in developing advanced refining technologies for REEs. Fortunately, progress is being made. Most recently, it was announced that Australian-based Lynas will become the first producer of “heavy” rare earths outside of China.

However, given the significant environmental impacts and land use concerns associated with REE extraction, there is strong evidence that the world must invest more in recycling. The benefits of recycling these materials are enormous — benefits that can hardly be overstated.

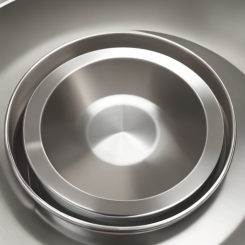

Recycling does not generate hazardous waste, and REEs are found in higher concentrations in recycled materials than in natural ore. Promising technological progress has also been made in this field recently. One notable development comes from young chemist Marie Perrin at ETH Zurich in Switzerland.

Perrin has developed a breakthrough process that recovers europium (one of the REEs) from discarded fluorescent lamps. The innovative process begins with disassembling the lamps to extract the phosphor powder. The powder is then dissolved in acid, and by introducing sulfur-based molecules, a solution rich in REEs is obtained.

Perrin’s research team is also working on scaling this technology to handle other REE waste streams, with a continued focus on recycling.