Rich metal deposits on the seafloor could power the clean energy transition – but at what ecological cost? Increasing debate on untapped resources and unresolved questions emerges.

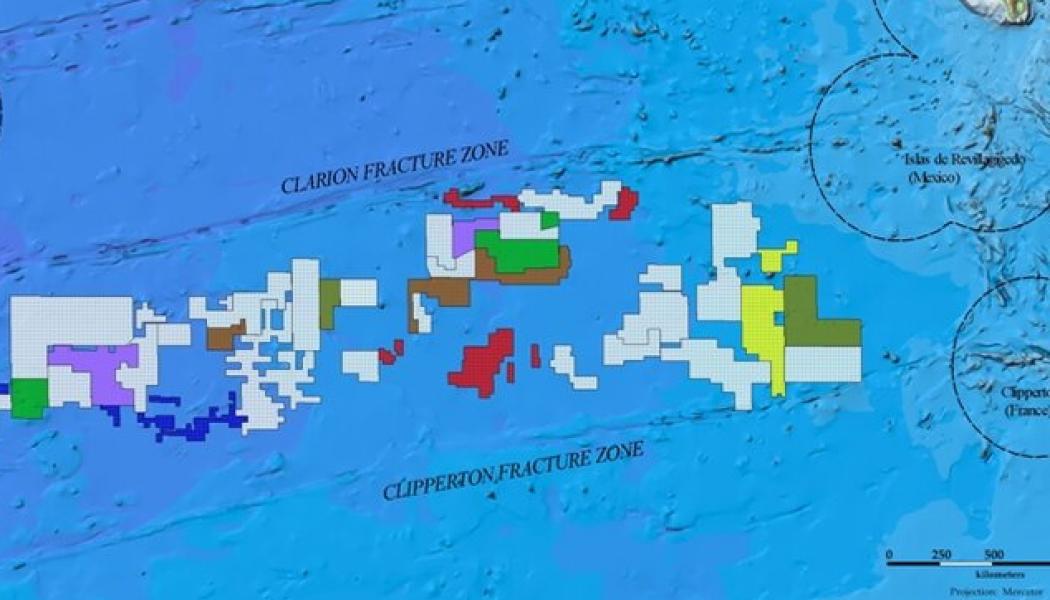

Vast amounts of nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese lie on the deep seafloor, particularly in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the Pacific Ocean. These metals are essential for electric vehicle batteries and the broader energy transition. Some believe deep-sea mining could ease future supply shortages – others warn of irreversible damage to fragile ecosystems.

– We know very, very little about how the deep sea functions, but we know it’s fragile – said Jessica Battle, who leads the World Wildlife Fund’s No Deep Seabed Mining Initiative.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN-affiliated body that oversees mining beyond national waters, recently missed a key deadline to finalise mining regulations. As a result, it must now process applications without a complete rulebook. Canadian firm The Metals Company says it plans to submit the first such application in July 2024, aiming to begin operations in 2025.

A controversial path to clean energy metals

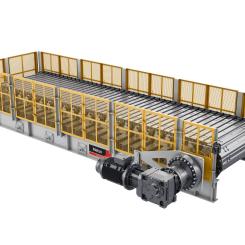

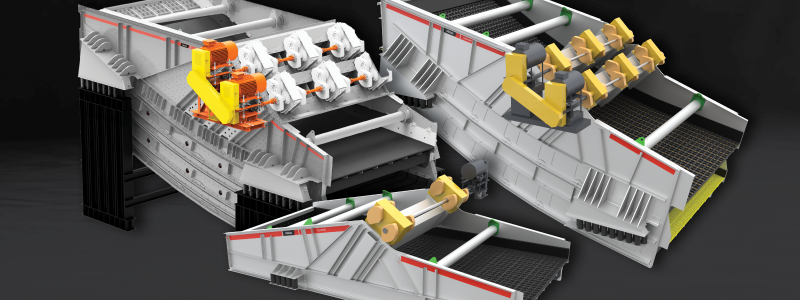

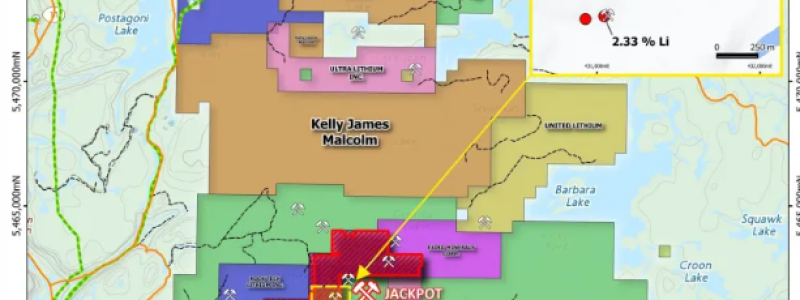

Demand for nickel is expected to grow twentyfold by 2030, cobalt fourfold, and manganese eightfold, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. These metals occur in polymetallic nodules – rounded mineral clusters covering up to 70 per cent of the CCZ seabed.

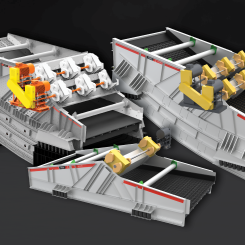

The Metals Company holds exploration rights in an area known as NORI, estimated to contain the world’s largest undeveloped nickel deposit. Together with a second site, the company claims its holdings could supply enough metals to produce batteries for 280 million electric vehicles – roughly equal to the number of cars on US roads today.

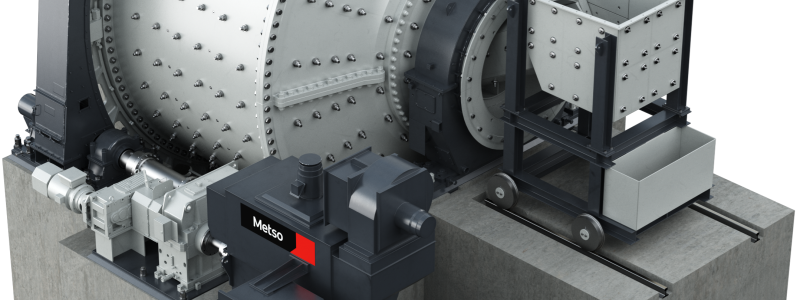

A recent life-cycle assessment, commissioned by the company, compared seabed mining to conventional land mining. The results suggest that emissions linked to mining and processing nickel, copper and cobalt from the seabed could be 54 to 70 per cent lower. The process also avoids blasting and harmful tailings. However, the analysis did not include impacts on marine biodiversity or sediment plumes – two major concerns for critics.

Biodiversity risks and regulatory uncertainty

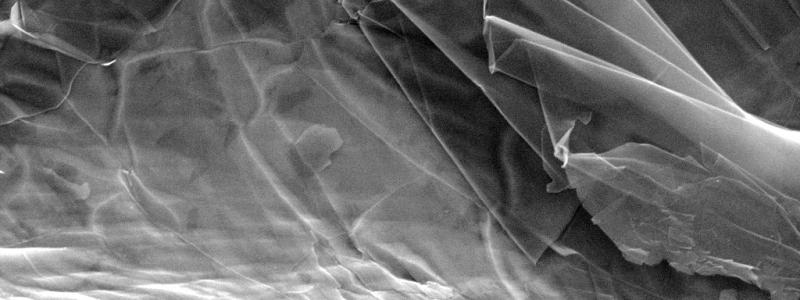

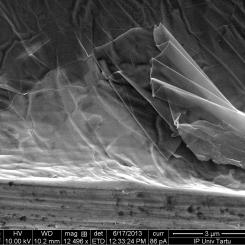

Many species living in the CCZ remain undocumented. Some rely directly on polymetallic nodules for shelter or food, raising concerns that their removal could destroy unique and little-understood habitats.

– Scientists say it could take decades before we understand enough to make informed decisions – said Battle.

Even The Metals Company acknowledges that thousands of species may still be undiscovered in the area. Images from recent expeditions have captured previously unknown organisms, including deep-sea corals, sea cucumbers and the gelatinous “gummy squirrel.”

Legal uncertainty also clouds the process. In 2021, the island nation of Nauru triggered a rule requiring the ISA to finalise regulations within two years. That deadline passed in July 2023. Whether the ISA can now approve mining under draft rules is still debated. The Metals Company argues that the draft regulations are far enough along to serve as a basis for review.

– We think they’re sufficiently advanced to guide decisions on incoming applications – said CEO Gerard Barron.

But legal experts, such as Pradeep Singh from the Research Institute for Sustainability, disagree.

– The ISA hasn’t even defined what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable environmental harm – Singh said – It could take years before all 36 member states agree on a final framework.

Meanwhile, more than 20 major companies, including Google, Samsung, BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo, have backed a moratorium on deep-sea mining, citing the scientific uncertainty.

At the same time, The Metals Company is under pressure to show progress. A 2021 SPAC merger left it short of promised funds, and its share price has fallen by nearly 90 per cent. Maersk, once a major shareholder, divested in 2023.

– These projects need to prove their business case soon – said Benchmark COO Andrew Miller – Capital is not unlimited.

Whether deep-sea mining becomes a key part of future metal supply or a cautionary tale of ecological risk will depend on the coming years – and on decisions yet to be made.

Source: CNN, WWF, The Metals Company, Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, ISA