Norway’s ambitions to mine minerals from the Arctic seabed remain in limbo following the government’s decision to delay its first licensing round. Originally expected in 2024, the process is now scheduled for 2026.

The delay has had tangible effects — one deep-sea mining company has gone bankrupt, another has halved its workforce. Yet others, including Bergen-based Adepth Minerals, say they remain committed to preparing for eventual exploration.

– I’m not worried about the future of deep-sea mining – said Anette Broch, CEO of Adepth Minerals – We believe the government will move forward.

Still, opposition is growing. Environmental groups, the fishing sector, and several political parties argue that the ecological risks are too high and the knowledge base too thin. At a recent industry conference in Bergen, Greenpeace staged protests likening deep-sea mining to “gambling with the ocean.” A survey commissioned by Greenpeace found that only eighteen per cent of Norwegians support seabed mining.

– We’re talking about sending machines into Earth’s last untouched wilderness – said Greenpeace Norway’s Haldis Helle – It’s completely reckless.

Political friction and uncertain futures

Although Norway’s parliament approved initial exploration in 2024, opposition parties — notably the Socialist Left Party — succeeded in halting the licensing round through budget negotiations. Whether the process resumes as planned in 2026 remains unclear, especially with national elections approaching.

Some companies are adapting. Green Minerals, publicly listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange, cut its budget by eighty per cent and replaced its CEO. Others, like Loke Marine Minerals, collapsed entirely, filing for bankruptcy in April 2025 after acquiring licenses in international waters.

Industry actors say delays and political instability undermine investment. Still, the government has increased funding for environmental and mineral mapping — from thirty million to one hundred fifty million kroner — signalling continued interest.

– The first licensing round is planned for 2026, with potential awards in 2027 – said Lars Erik Aamot of the Ministry of Energy – What happens after that depends on the results from the exploration phase.

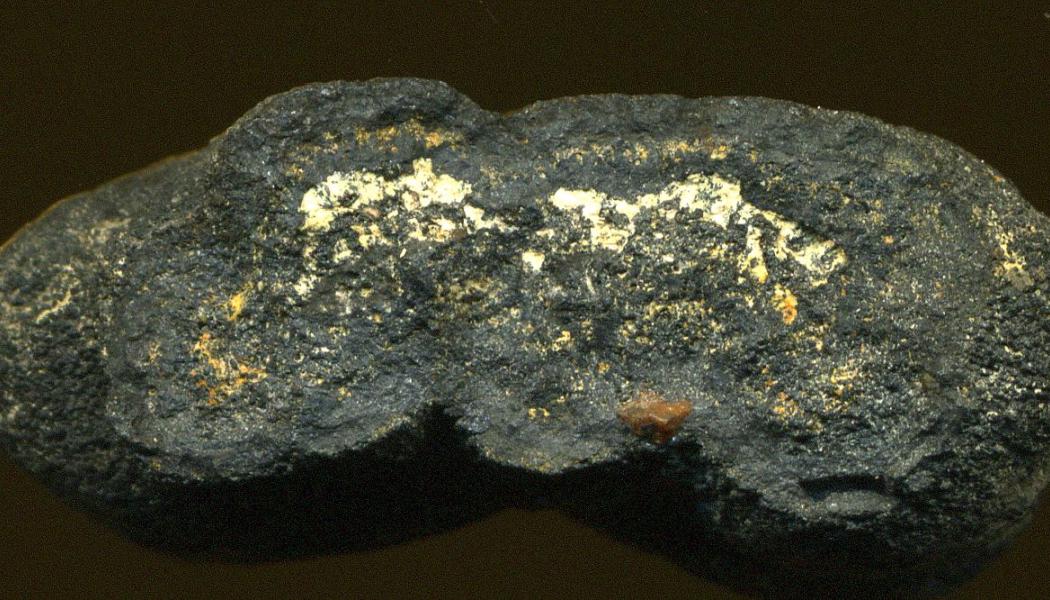

Knowledge gaps and environmental concerns

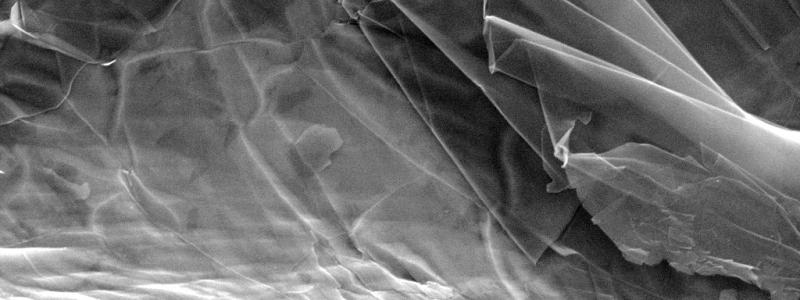

Marine scientists emphasise that many questions remain unanswered. Researchers such as Pedro Ribeiro at the University of Bergen are still identifying species in proposed mining zones, including hydrothermal vents and seamounts above the Arctic Circle.

– We don’t yet understand how these ecosystems are connected – said Ribeiro – or how they might respond to sediment plumes from mining.

His colleague Pål Buhl-Mortensen at the Institute of Marine Research agrees that Norway’s seabed remains largely unmapped. Although the national MAREANO program is one of the world’s most advanced, it has only fully mapped around ten per cent of Norwegian waters.

Meanwhile, companies are exploring options outside Norway. Adepth Minerals may shift focus to international waters if domestic licensing stalls. Green Minerals has already signed a memorandum of understanding abroad, while TMC — a Canadian company — is pursuing mining approval through the United States instead of the United Nations system.

Whether Norway will become the first country to start commercial deep-sea mining remains uncertain. Political resistance, scientific caution, and investor hesitation continue to shape the timeline. Yet with critical minerals in global demand, the debate is far from over.

Source: Mongabay / Ocean Reporting Network, supported by the Pulitzer Centre