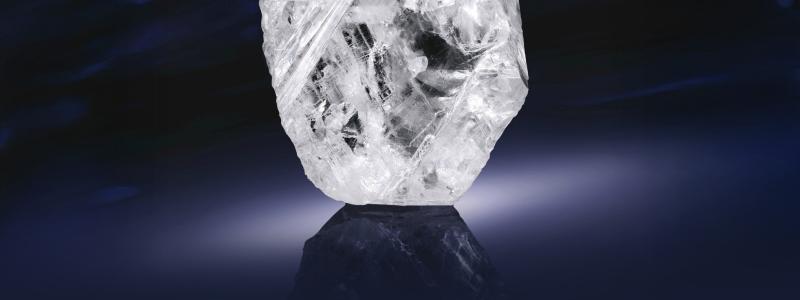

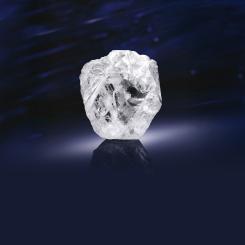

A new discovery of rare earth elements in southeastern Norway could have major implications for Europe’s mineral independence. The mining company Rare Earths Norway (REN) has identified 8.8 million tons of rare earth oxides in the Fen region – the largest known deposit on the European continent.

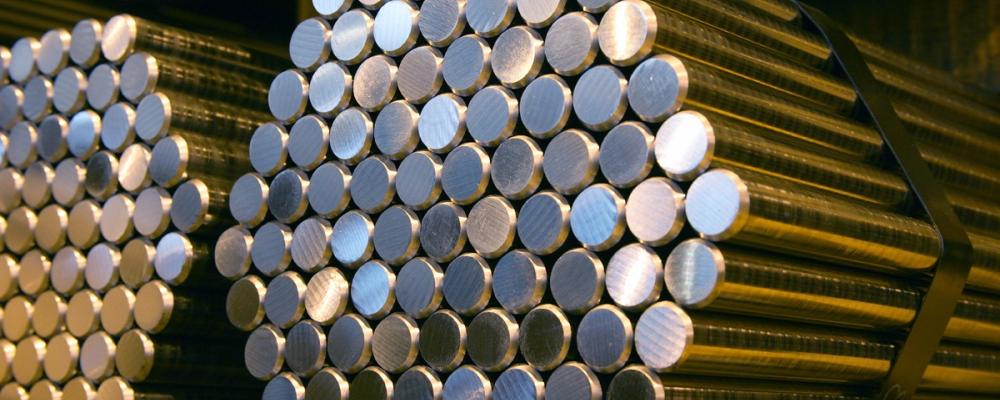

Rare earth elements comprise 17 metals used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, electronics, and defence systems. Despite their name, they are not particularly scarce in the Earth’s crust – but mining and refining them is complex, polluting, and concentrated in a handful of countries.

– Two main problems define this market: its environmental impact and the concentration of players, especially in China, says Emmanuel Hache, Senior Research Fellow at IRIS and an expert in energy resources.

Strategic metals, not so rare after all

At current production levels of around 350,000 tons per year, global reserves could last more than 300 years. Yet China controls nearly 69 per cent of mining and 88 per cent of refining capacity – leaving Europe vulnerable to supply disruptions.

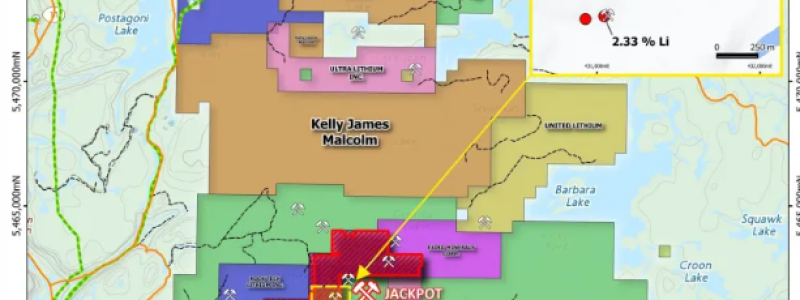

REN’s Norwegian discovery follows LKAB’s 2023 find in Kiruna, Sweden, where more than one million tons of metals, including rare earths, were identified. Together, these discoveries could help the EU build a more secure and autonomous supply chain.

Small market, big geopolitical weight

The global rare earth market is relatively small compared to copper, but geopolitically vital. These metals are indispensable for low-carbon and digital technologies, particularly the permanent magnets that power wind turbines and electric vehicles – already accounting for more than half of total demand.

– Deng Xiaoping’s remark, “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths,” perfectly captures Beijing’s long-term strategy, says Hache. – It also highlights the West’s short-term mindset: outsourcing environmental costs instead of securing its own resources.

Among OECD members, only the United States, Australia, Canada, and Greenland hold significant reserves. That makes the Norwegian deposit – equivalent to roughly 1.5 million tons of material for EV and wind turbine magnets – a major strategic asset for Europe.

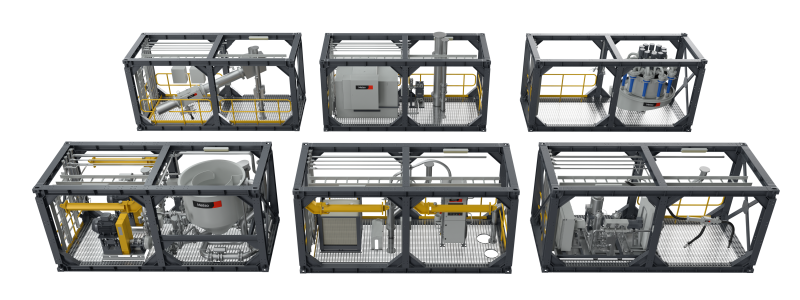

Long road to production

In her 2022 State of the Union address, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen warned that Europe’s demand for lithium and rare earths would increase fivefold by 2030. Today, the EU relies on imports for more than 98 per cent of its needs, mostly from China.

The EU’s new Critical Raw Materials Act, adopted in April 2024, aims to reduce this dependency by setting production and processing targets: 10 per cent of demand must come from domestic extraction and 40 per cent from European refining.

REN plans to invest around 10 billion Norwegian kroner (about 870 million euros) to launch the first mining phase by 2030, potentially supplying 10 per cent of Europe’s total consumption. But the path ahead is long, facing both environmental and economic hurdles.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global demand for rare-earth-based permanent magnets could double by 2050, even under Paris-compliant climate scenarios.

This means that even with Norway and Sweden’s new finds, Europe will not quickly overcome its import dependence. Recycling and resource efficiency must therefore play a central role alongside new mining projects.

– Discoveries are just the beginning, says Emmanuel Hache. – The real challenge is to build a European value chain that meets environmental standards while competing with China.

Facts:

- Norway now holds Europe’s largest known rare earth deposit.

- China accounts for 69 per cent of global mining and 88 per cent of refining.

- The EU targets 10 per cent of its consumption from domestic extraction.

Source: IRIS France, interview with Emmanuel Hache.